Folk Cookery from the English Countryside

Lally Macbeth on the binding importance of the English Cake

In her new book, The Lost Folk, the author Lally Macbeth examines the role folk culture has played in our history. She argues, too, that we should embrace it anew, as a unifying force, in our fractured times.

In this excerpt from the book she recounts the stories of Barbara Jones and Florence White. Both of these were gifted collectors who found deep meaning in everyday English food.

With an introduction by Lally McBeth

In this extract from The Lost Folk, we look at two lost collectors: Barbara Jones and Florence White. Both concerned themselves, in part, with the collection of folk cookery and food. Food is ephemeral by its nature, and both Barbara and Florence managed to find ways in which to collect and display food connected with folk customs and practices.

– Lally McBeth

For references please consult the finished book.

Someone who really understood the principle of collecting as an art form was the artist and writer Barbara Jones. Born in 1912, Barbara wrote and illustrated numerous books on folk art, including The Unsophisticated Arts (1951) and Follies and Grottoes (1953), painted many murals and illustrated a number of books for other writers, including In Trust for the Nation (1947) by Clough Williams-Ellis.

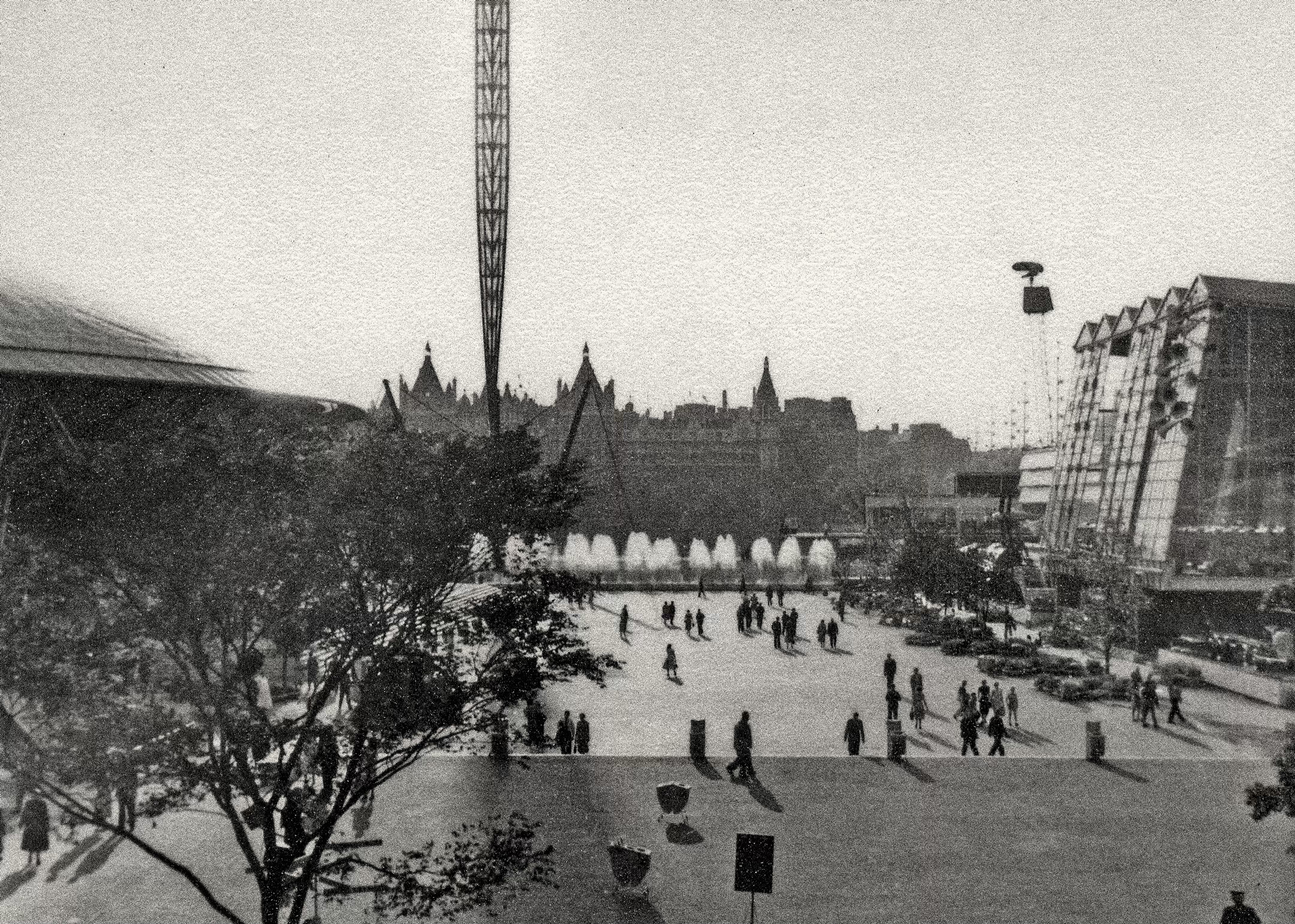

Above all else, however, she was an impassioned collector, and in 1951 she put into practice for the first time her ability to curate and formulate objects into a story. As part of the Festival of Britain, she was asked to curate an exhibition on the folk arts of Britain, when fellow folk collectors Enid Marx and Margaret Lambert turned the job down.

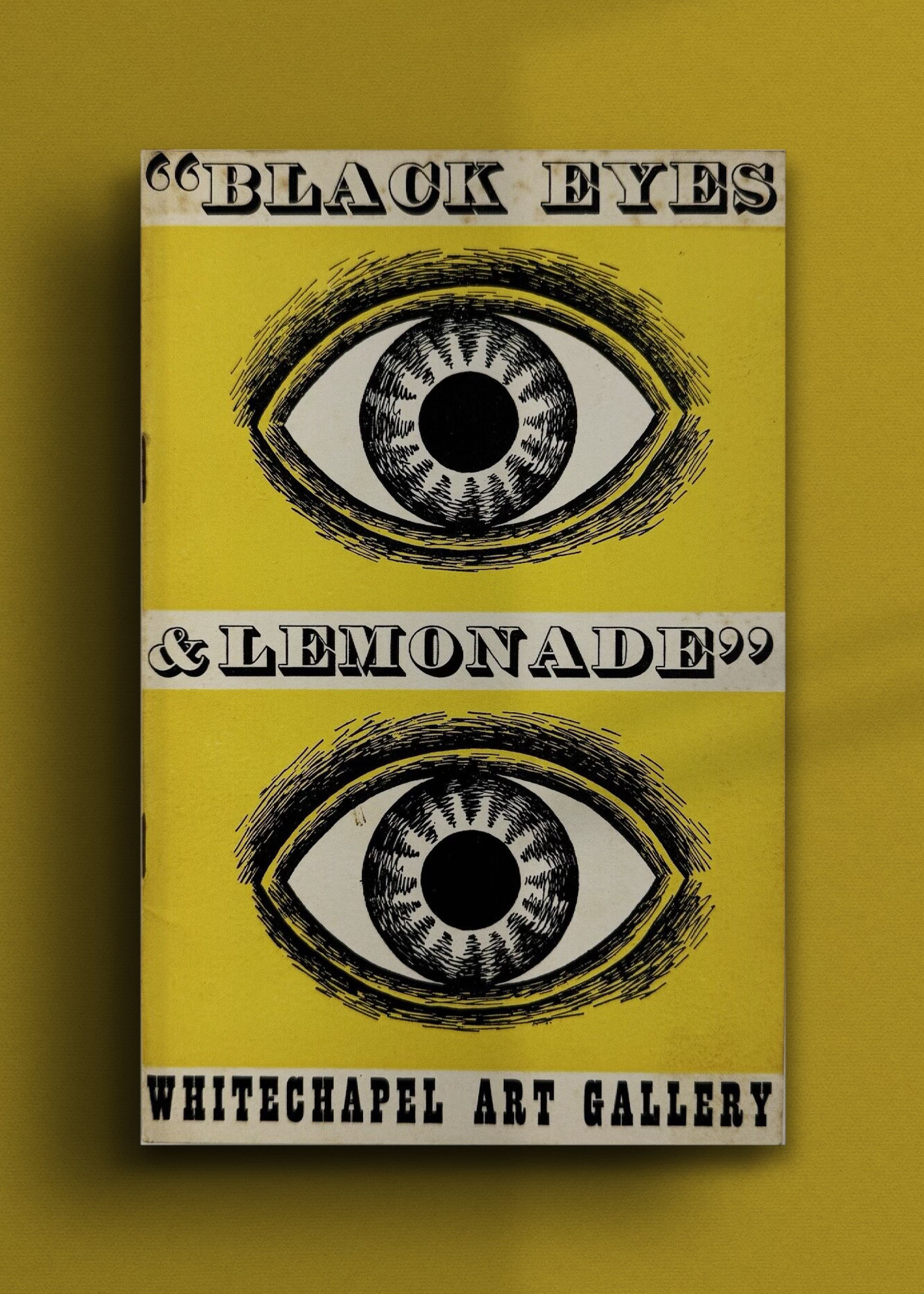

Barbara titled the exhibition ‘Black Eyes and Lemonade’ after a satirical line by the Irish poet Thomas Moore: ‘A Persian’s Heaven is easily made / Tis but – black eyes and lemonade.’ Barbara described the exhibition title as expressing ‘the vigour, sparkle and colour of popular art rather better than the words “popular art”’.

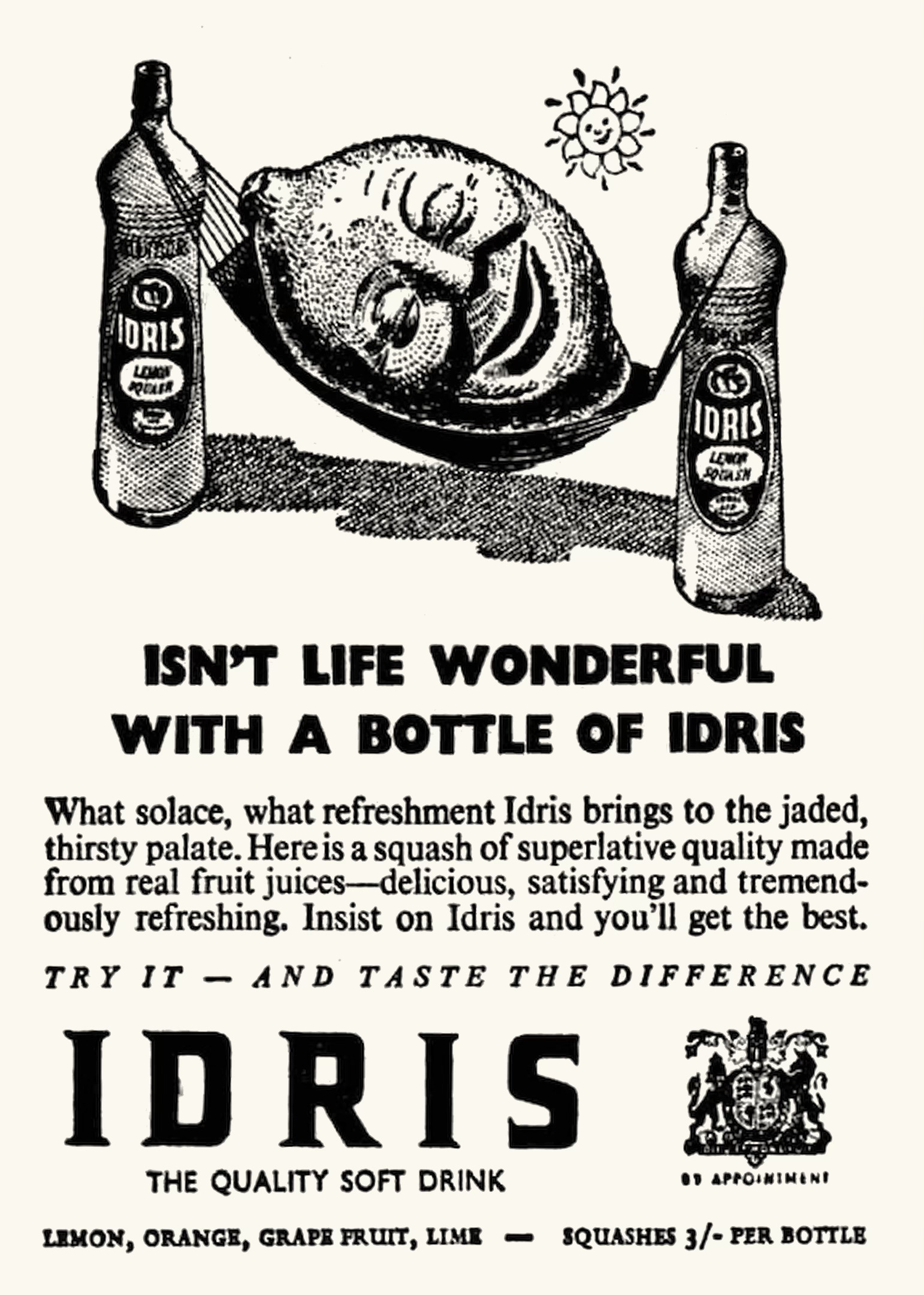

It also referred to two of the most infamous exhibits of the exhibition: a pair of illuminated glasses that had been part of an optician’s sign, and a talking lemon from the Idris lemonade adverts. The exhibition ran from August to October at the Whitechapel Gallery in London and was an extraordinary success, with more than thirty thousand visitors.

Barbara, ever the innovator, was most insistent that it be titled ‘popular art’ rather than ‘folk art’, allowing her to celebrate all aspects of folk culture, both handmade and mass produced. You may wonder why she included mass-produced objects: surely these aren’t folk objects, when the mark of the hand is deemed one of the defining features of folk?

Barbara believed that some mass-produced objects did firmly sit in the category of folk. She asserts in the catalogue introduction that ‘there is a dividing line between tool (allowed as hand) and machine, but it is very difficult to say exactly where, and so far, a human brain has always dictated just what the machine shall produce’.

Her argument for their inclusion was unpopular – the exhibition sponsors, the Society for Education in Art and the Arts Council, were strongly against their inclusion due to the cheap production methods used and the generally crude or tawdry aesthetic of the objects.

This is an argument that occurs frequently in relation to all folk objects. They are often made with cheap materials that are to hand, and without longevity in mind. They are, of course, also generally made to be used. Therefore they can sometimes look fairly weathered by the time they make it to the museum or exhibition space, rather throwing out of the window normal curatorial or preservation practice.

We often expect museum or exhibition objects to look perfectly preserved, but this is just not the case with many folk objects. They are generally fraying at the seams, faded and crumpled, and that in many ways is part of their charm; they have had an active life and are imbued with all the stories and marks that come with that.

The catalogue for ‘Black Eyes and Lemonade’ makes it clear that Barbara also included many items that had not had an active life but would have an ephemeral one after the exhibition: cakes, biscuits and bread made up large swathes of the displays. There was a three-tiered wedding cake, a selection of harvest loaves in such shapes as a wheatsheaf and a horn of plenty, and a variety of models made in royal icing in the shape of everything from St Paul’s Cathedral to a stagecoach.

The makers of these confections were all listed by name and often also by place. They were messy objects, and liable to collapse, melt or drip, but in Barbara’s fizzing lemonade mind they were essential to a proper telling of popular art in Britain. In the Whitechapel Gallery archive there is an image of two children being handed pieces of one of the exhibits; the little boy licks icing from his fingers. This was truly living folk art.

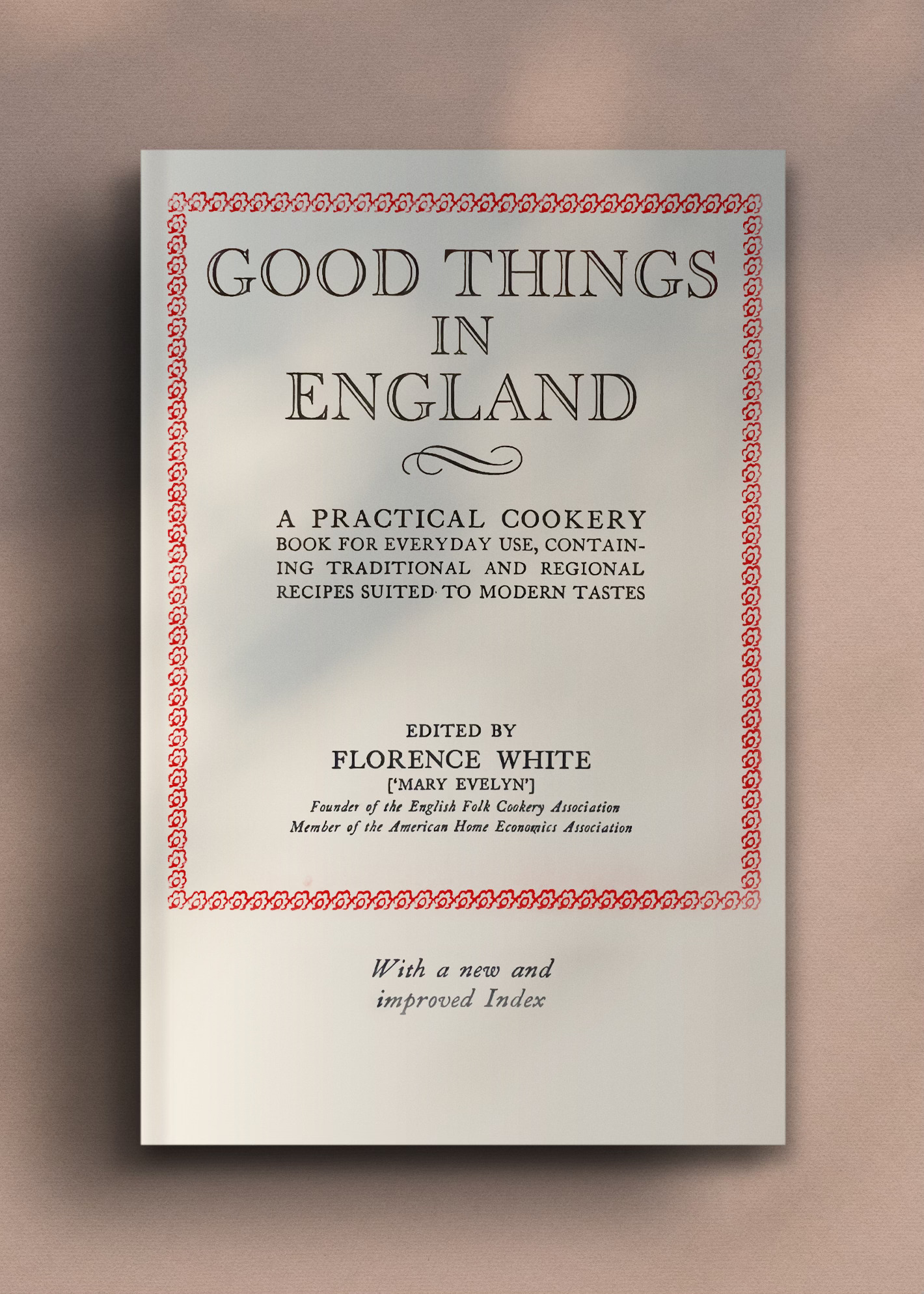

Barbara, however, was not the first person to display food in this way. In 1928 the cook, writer and teacher Florence White began a group called the English Folk Cookery Association. It was set up with the aim of celebrating and teaching people traditional folk cookery methods, from how to make everything from Ripon spice bread* to frumenty.†

Florence was deeply influenced by an exhibition that took place in 1891, put together by the folklorist Alice Bertha Gomme: a selection of ‘Feasten Cakes’ for the International Folklore Congress held at Burlington House, London.

In an article titled ‘Folk Cookery from the English Country-Side’, Florence states, ‘Lady Gomme’s pioneering research work in English folk cookery must not be forgotten, especially as her interest is still living and active,’ and in the entry for ‘Fourses Cake’ in Good Things in England she mentions Alice’s involvement with the conference:

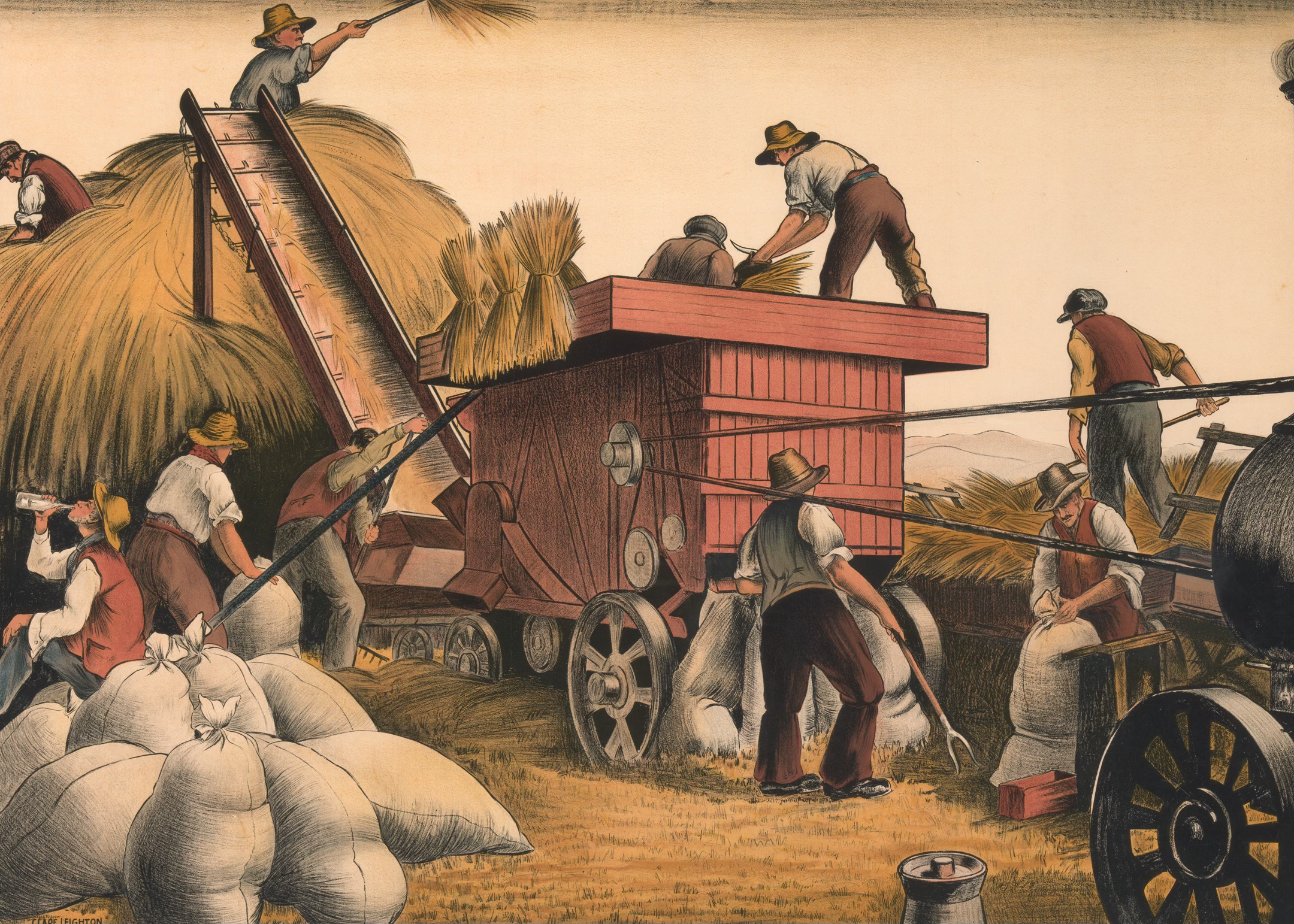

‘This is a cake made of yeast bread, lard, currants, sugar, and spice, eaten by Suffolk harvesters at 4 o’clock. One was included in the collection of local and ceremonial cakes shown by Lady Gomme at a Conference of the Folk Lore Society held in London in 1892.’

Like Florence, Alice had collected together cakes from across the British Isles, but her emphasis was very slightly different: she concentrated her efforts solely on cakes used in folk practice in some way or as part of folk customs that were just about still in use when she collected them, yet in danger of dying out.

There were celebratory cakes such as Welsh Easter cakes and Cornish christening cakes, harvest cakes from Devonshire and soul cakes from Staffordshire, hollow biscuits from Norfolk and, interestingly, Turkish funerary biscuits made by a Miss Lucy Garnet.

Each was labelled with its particular county. The locality was key to their importance. An article at the time, from the journal Folklore, suggests that collecting them together was not without its difficulties: ‘A very large number of commemorative cakes have disappeared from local custom in England, but the entertainment committee have obtained as many as could be procured, in the hope that attention may be directed to these interesting relics of bygone custom.’

The International Folklore Congress was the first meeting and exhibition of its kind to be held in Britain. It was hosted by the Folklore Society and brought together all the major folklorists working in the British Isles in the late nineteenth century.

As chairman of the committee Alice’s husband, the folklorist George Laurence Gomme, was instrumental in planning who spoke and what was chosen for the exhibitions, and so Alice was in charge of not only the feasten cakes but also, alongside Charlotte Burne, organising an evening of demonstrations of traditional children’s games and songs (in which she was an expert), folk songs and dances.

The evening was entitled ‘Conversazione’ and was held at the Mercers’ Hall in London. All the songs and dances chosen were still being performed at that time, which allowed them to be performed by children and adults who danced and sang them in daily life. It was not an exercise in re-enactment but instead an acknowledgement of contemporary folk practice and the need to collect the present.

Alice’s influence could be felt throughout the exhibition, and many of the more maverick aspects of the weekend seem to have her touch. A review of the congress in the Journal of American Folklore suggests, for instance, that the cakes were not only on display but also that ‘a sufficient quantity of these had been provided for refreshment at afternoon tea during the congress’.

Not only could these cakes be admired and pontificated over, but they could also be consumed, and this is an important point: Alice came from a school of folklorists that believed in fully engaging themselves in order to understand the custom or tradition properly. Interestingly, Cecil Sharp often cited her as a major influence on his work, and indeed as the reason he started collecting folk songs and dances, but she was far more akin in her practice to Mary Neal or Dorothy Hartley.

In many ways, Alice was before her time: she highlighted the folk practice of women and children when nobody had even considered things like skipping or counting games or folk cookery important to preserve.

In 1931, Alice Gomme became the president of the English Folk Cookery Association, and the next year, Florence’s magnum opus, Good Things in England, was published, in which she dedicated a large section to the making of English cakes.

Out of this research came her own fleeting exhibition inspired by Alice’s: ‘100 English Cakes’. It has left almost no trace. The objects, of course, all being edible and therefore perishable, did not survive. I’ve not been able to find any photographs of the exhibition, and there is barely any other evidence.

There are several pamphlets that survive in Hampshire County Council’s archive for Florence’s English Folk Cookery School, which she began in 1936. This was based at 160 West Street in Fareham, Hampshire, and the pamphlets make reference to an ‘exhibition window’, so it could be presumed that this shop was the location for her exhibition of cakes but it was in fact, like ‘Black Eyes and Lemonade’, held in the heart of London at a lecture hall at 30 Kensington Church Street.

The Daily Telegraph describes it as containing ‘Burial Cakes, Yules Doos, Sedgemoor Easter Cakes and Checky Pigs’. It is not known what was shown in the English Folk Cookery School ‘exhibition window’: perhaps more cakes made by her budding students, or perhaps other even less well-documented exhibitions of cakes.

Although the article only makes reference to a small amount of the confections on show, we can establish what the other cakes might have been thanks to Good Things in England, where there is mention of fried cakes, Shrewsbury cakes, revel buns, Lancashire parkin and Portland cake, among many others.

What is trickier to guess at is the way in which Florence might have chosen to display them. Were they tiered? Or in lines? We may never know. It’s also difficult to imagine what some of the cakes might have looked like: what, for instance, is a checky pig?

Thankfully one other review in the Daily Herald makes mention of them as ‘little pigs modelled out of dough and stuffed with mincemeat’. Neither of the articles makes any reference to how long they were exhibited for, or whether they were consumed at the end. Florence’s cakes have almost entirely vanished from memory •

This excerpt was originally published June 20, 2025.

* Ripon spice bread is a yeasted cake from Ripon, North Yorkshire. The recipe was collected from Mr Herbert M. Bower.

† Frumenty is a spiced and sweetened porridge traditionally eaten with venison.

The Lost Folk: From the Forgotten Past to the Emerging Future of Folk

Faber, 19 June, 2025

RRP: £19 | ISBN: 978-0571388301

“A splendid museum full of strange and wonderful things”– Peter Ross

A fresh and engaging celebration of the customs, places, objects and peoples that make up what we know as 'folk' in Britain.

By its nature, folk is ephemeral: tricky to define, hard to preserve and even more difficult to resurrect. But folk culture is all around us; sitting in our churches, swinging from our pubs and dancing through our streets, patiently waiting to be discovered, appreciated, saved and cherished.

In The Lost Folk, Lally MacBeth is on a mission to breathe new life into these rapidly disappearing customs. She reminds us that folk is for everyone, and does not belong to an imagined, halcyon past, but is constantly being drawn from everyday lives and communities. As well as looking at what folk customs have meant in Britain's past, she shines a light on what they can and should mean as we move into the future - encouraging us to use the book as an inspiration, and become collectors and creators of our very own folk traditions.

“Erudite, questing and endlessly fascinating . . . the book that British folk has long needed”

– Katherine May

With thanks to Lauren Nicoll. Author Photograph © Matthew Shaw.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store