1892: Tower Bridge, London

At the end of the nineteenth century the gaunt arms of an engineering wonder stretched across the River Thames

In the first years of the 1890s the rising form of Tower Bridge was one of the great sights to see in London. Here, on a bitterly cold winter’s day – most likely January of 1892 – we can glimpse the extraordinary scene anew. There is the noble old river, strewn with shipping of all types. And then, rising upwards in a tangle of iron and scaffolding, is a bridge unlike any other. The north and southern portions of this extraordinary engineering project are poised to meet.

Words by Peter Moore

Photographs Remastered & Colourised by Jordan Acosta

Five and a half years before this photograph was taken, on 21 June 1886, Edward, the Prince of Wales, laid the foundation stone for the new bridge on the northern bank of the Thames. Having arrived in a state carriage that had been cheered all the way from Marlborough House, Edward told the gathered crowds that he believed the new bridge would be ‘of great utility and convenience to the public in relieving the congestion of traffic across the river’.

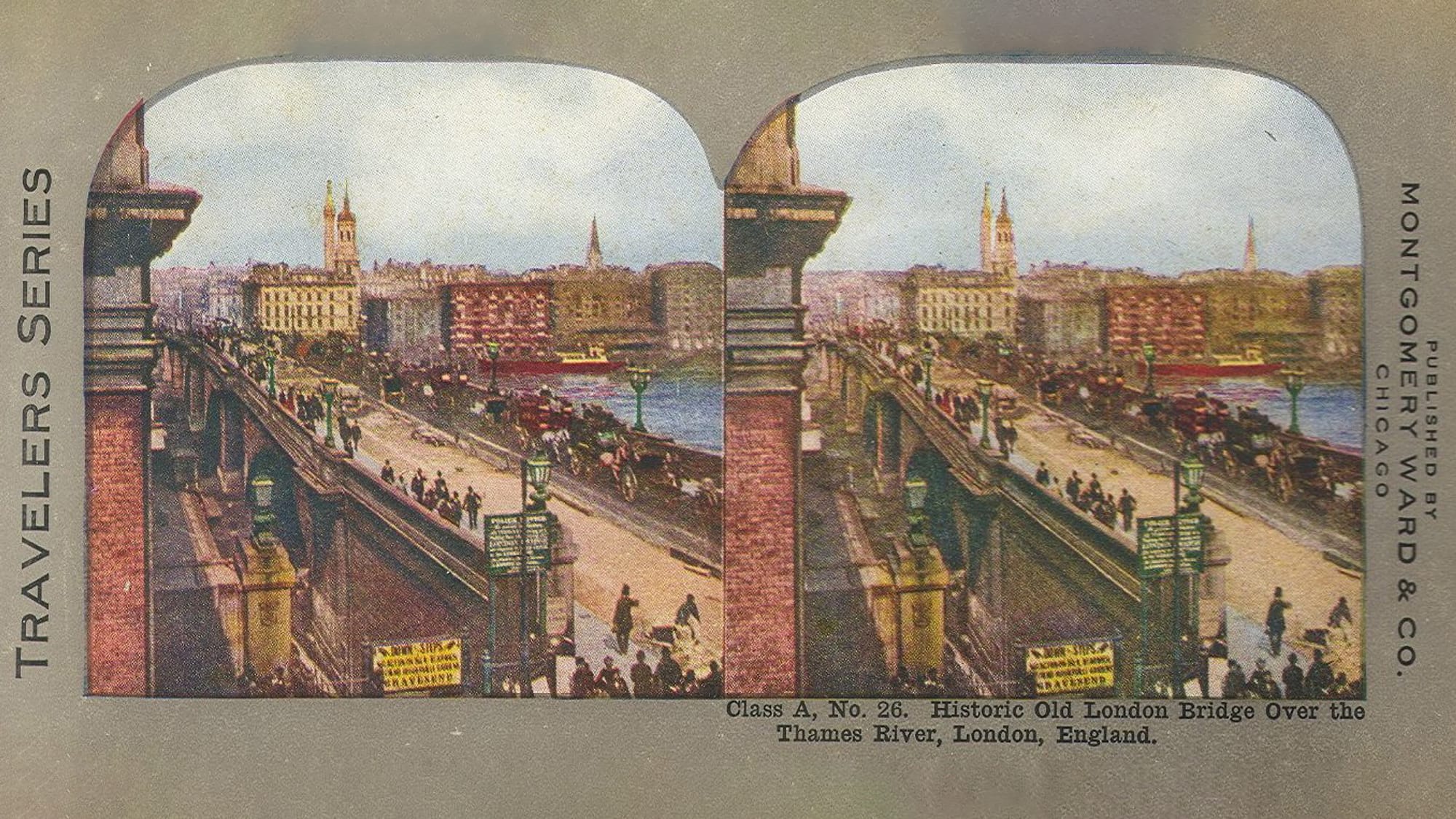

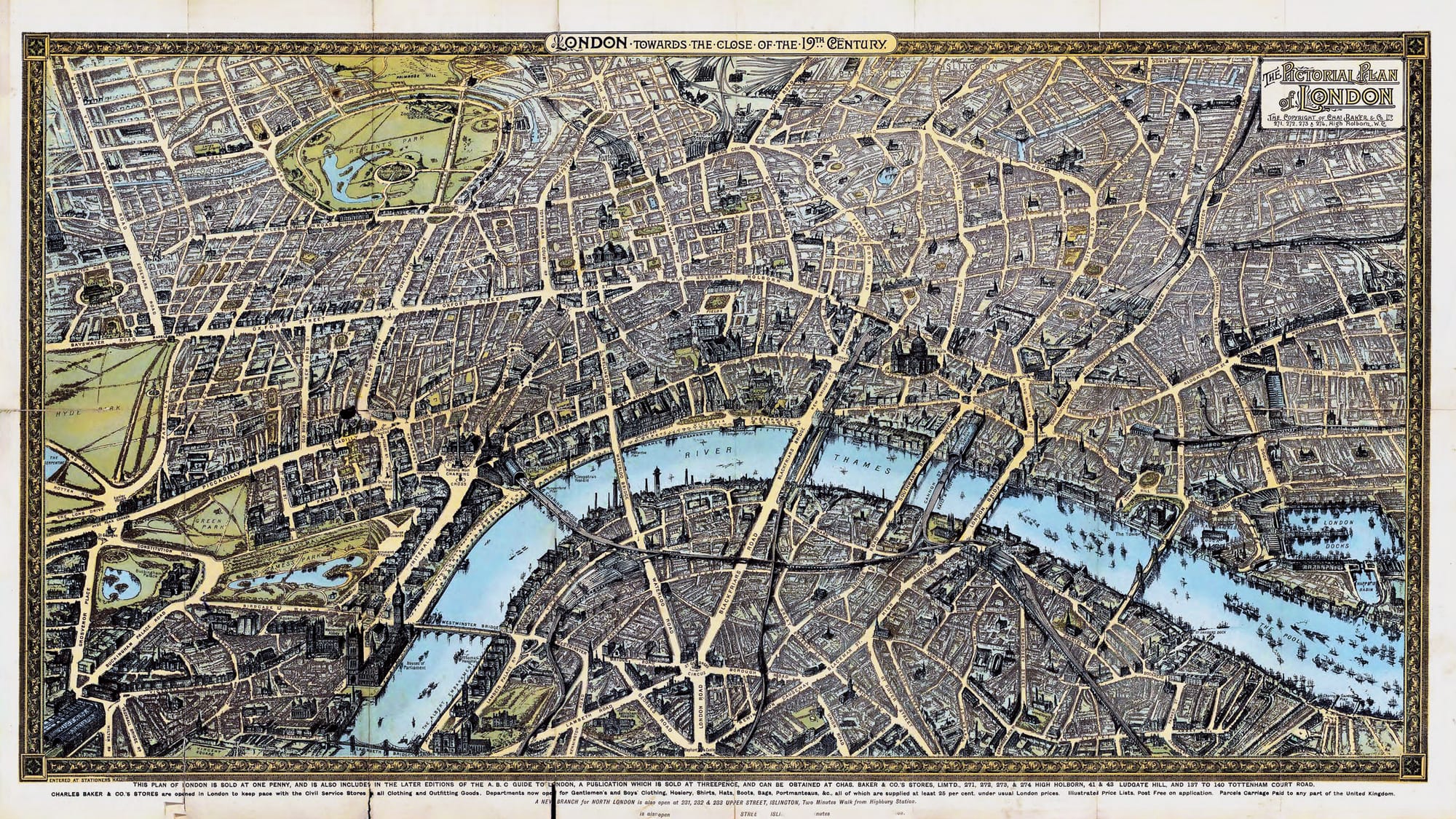

Some traces of the congestion the prince alluded to can be seen in the colourised photograph above. For centuries London Bridge, between the City and Southwark, had been the easternmost crossing. Those needing to pass from north to south downstream of the Tower of London were left with the choice of a roundabout journey up to town or a choppy crossing in one of the rowed ferry boats.

As the population of the imperial capital surged in the Victorian Age, this situation became increasingly intolerable and by the 1880s there was a clear need for a new bridge near the Tower of London.

The task, however, was a challenging one. Much of London’s heavy shipping plied upstream as far as the Custom House and to construct a regular bridge would be to isolate a significant stretch of the busiest commercial waterway in the world.

Various plans were generated and by 1889, three years after the foundation stone was laid, Londoners were at last able to see the outline of a project that was already being called an engineering wonder. Two river piers had been sunk: one at Little Tower Hill on the northern bank, the other on the Bermondsey shore.

These piers were in themselves remarkable. They both stood in London clay at a depth of 60 feet beneath the Thames’s high water mark. Their base was 200 feet long by almost 100 broad. When the bridge that would join the two was complete its total span would be 940 feet and once the two approaches were taken into consideration this number would swell to 2,640. More than 31 million bricks were to be used, 19,500 tons of cement along with 235,000 cubic feet of granite and other stone.

All this sounded impressive. But a deeper source of excitement for those who gazed at the bridge was the understanding that this was a machine as much as anything. It was to be installed with two steam pumping engines of 360 horsepower each that would drive the hydraulic machinery that would lift the two leaves of the central section, which worked on the bascule or drawbridge principle. Once opened ships would be allowed to pass. To see these leaves swing open, predicted one journalist in 1891, ‘will be one of the sights of London.’

By the time these words were written Londoners could clearly perceive the new bridge’s idiosyncratic form. Having probed outwards into the river, both the northern and southern sections had reached a point where they started to progress upwards.

Four tubular iron columns on each side rose to 135 feet, the height of the high level footway or ‘aerial pathway’. In time the iron columns would be covered by the granite of the towers, which would look to the fanciful eye like something out of a medieval castle.

It was during the months that followed that the above colourised photograph was taken. This was a time of great activity and progress. Large numbers watched on from the best vantage point on London Bridge. In the spring of 1892, one newspaper commented:

23 April 1892

The Tower Bridge will attract a great deal of attention during the next month. The upper footway is thrusting out from each of the lofty towers, and on each side overhangs the water to the extent of almost one-third of the space to be covered, leaving a gap of, perhaps, 60 or 70 feet between them. Viewed from London Bridge it looks to be most perilous work, the overhanging portions of the platform looking as though the weight of two or three workmen at the outer extremities would be sufficient to bring it all down.

Several months more would pass before the two sections of the bridge united. By November of 1892 it was possible to cross the upper walkway, a short journey which required both a permit from the site engineer and ‘considerable nerve’. One journalist for the Globe, however, took up the challenge and set down a lively account for his readers as he set off up one of the staircases that led to the first floor of the towers.

25 November 1892

It is up these staircases that the route lies; but [it] is not to be supposed that it is as easy as walking upstairs. In the first place there is a good deal of clambering over heaps of wood and ironwork before you get to the ladder by which you reach the stair; and when you get to it you find it is, though solid and substantial, of the most primitive style.

There is no balustrade; and the ascent is hard work; on the one side you see the river stretching out before you, on the other a yawning chasm filled with ironwork. Here and there you have to pass men using heavy hammers; every now and then a huge revolving crane swinging round some heavy girders seems coming straight for you; and, indeed, you have to proceed cautiously and with a wary eye, for now and again there is a perfect hailstorm of bits of iron: while there is an ever present danger of one of the men’s hammer heads flying off, and here and there you walk through a shower of sparks as someone above is working at a smithy in mid-air.

The way is full of perils, and the progress slow. Soon the climbing becomes exceedingly fatiguing as you begin to mount upwards the steep and apparently never ending staircase which leads to the first stage. There is less obstruction here, but you begin to feel dizzy, and by the time you reach the first tower you are glad, indeed, to welcome it as a haven of rest.

Given the dangers of labouring in such an environment, the journalist noted the astonishing fact that not one of the workers had died during the construction. In March 1894 the bascules of the bridge were lowered for the first time and in July of that year Edward, Prince of Wales, returned to the site once again to oversee its official opening.

The Tower Bridge, as it was called, had cost more than a million sterling that was paid for by the London Corporation. One of the great engineering projects in British history was complete.

📸 Dive into our Features

🎤 Read Interviews

🎧 Listen to Podcasts

🖼️ Buy fine art prints & more at our Store